In the realm of quantum physics, few frontiers are as tantalizing as the study of ultracold atoms. By cooling atoms to temperatures just a hair's breadth above absolute zero, scientists unlock bizarre and fascinating states of matter that defy classical intuition. These extreme conditions reveal quantum behaviors on macroscopic scales, offering a playground for probing fundamental physics and developing revolutionary technologies.

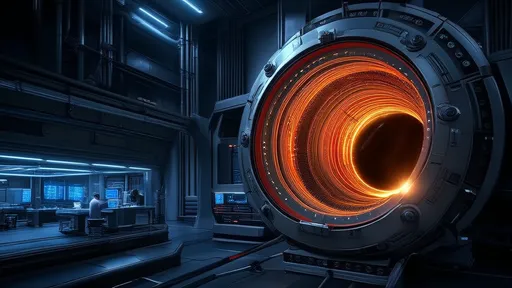

The journey to ultracold temperatures begins with laser cooling, a technique that uses the precise momentum of photons to slow atoms to a crawl. As atoms absorb and re-emit laser light tuned slightly below their resonant frequency, they lose kinetic energy in what amounts to a microscopic game of quantum ping-pong. This can cool atomic clouds to millikelvin temperatures - astonishingly cold by everyday standards, but still far from the quantum frontier.

To plunge deeper into the cold, researchers employ evaporative cooling in magnetic or optical traps. The hottest atoms are selectively removed, leaving behind an ever-cooler ensemble. Through this process, certain atomic gases can reach nanokelvin temperatures, where quantum statistics dominate behavior. At these extremes, the wave-like nature of particles becomes impossible to ignore, with atomic matter waves overlapping to form coherent quantum states.

One of the most striking manifestations of ultracold quantum matter is the Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC). When a dilute gas of bosonic atoms cools below a critical temperature, a macroscopic fraction of particles collapses into the lowest quantum state. This collective quantum state behaves as a single coherent matter wave, exhibiting properties like superfluidity and interference patterns that reveal its quantum mechanical origins. The 1995 creation of BECs in rubidium and sodium vapors earned Cornell, Wieman, and Ketterle the Nobel Prize, validating decades of theoretical predictions.

Fermionic gases tell a different but equally compelling quantum story. Due to the Pauli exclusion principle, identical fermions cannot occupy the same quantum state, preventing straightforward condensation. Yet through careful manipulation of interactions using Feshbach resonances - where magnetic fields tune atomic scattering properties - researchers can coax fermions into pairing and forming superfluid states analogous to Cooper pairs in superconductors. These strongly interacting Fermi gases model phenomena from neutron stars to high-temperature superconductors.

Optical lattices, created by interfering laser beams, provide perhaps the most versatile tool for quantum simulation with ultracold atoms. These periodic potentials can mimic the crystalline structures of solid-state materials, but with unprecedented control. By adjusting lattice depth and geometry, physicists can recreate textbook models of condensed matter physics like the Hubbard model, studying quantum phase transitions and exotic magnetic ordering in pristine, defect-free environments impossible to achieve in actual crystals.

The clean isolation and tunability of ultracold systems make them ideal for exploring many-body quantum phenomena. Quantum magnetism, topological phases, and many-body localization can all be engineered with appropriate combinations of optical potentials and interatomic interactions. Recent experiments have even realized synthetic dimensions and artificial gauge fields, effectively creating magnetic effects for neutral atoms and opening pathways to study quantum Hall physics without the need for charged particles or strong magnetic fields.

Precision measurement stands as another major application of ultracold atomic physics. Atomic clocks based on optical transitions in laser-cooled atoms or ions now keep time with staggering accuracy, losing less than a second over the age of the universe. Matter-wave interferometers using BECs promise even more sensitive measurements of inertial forces, potentially revolutionizing navigation and fundamental tests of general relativity. The extreme control over quantum states also enables new approaches to quantum information processing, with neutral atoms emerging as promising qubit candidates for quantum computers.

Looking ahead, the field continues to push boundaries. Quantum gas microscopes now image individual atoms in optical lattices with single-site resolution, while cavity quantum electrodynamics merges the control of ultracold atoms with the manipulation of single photons. Hybrid systems that interface ultracold atoms with other quantum platforms - superconducting circuits, nanomechanical oscillators, or solid-state spin systems - may enable entirely new functionalities. As techniques for cooling and controlling atoms grow ever more sophisticated, so too does our ability to explore and harness the quantum world.

From revealing the fundamental nature of quantum matter to enabling technologies that will shape the 21st century, ultracold atomic physics represents one of the most dynamic frontiers in modern science. Each advance in cooling and control peels back another layer of quantum reality, bringing us closer to answering age-old questions about the nature of matter while developing tools that will transform how we measure, compute, and understand our universe.

By /Jun 20, 2025

By /Jun 20, 2025

By /Jun 20, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025

By /Jun 19, 2025